| Login | ||

Healthcare Training Institute - Quality Education since 1979

CE for Psychologist, Social Worker, Counselor, & MFT!!

Section 26

Loss & Bereavement and How the Creative Arts Can Help

Part II

Question

26 | Test

| Table of Contents

James

For my next case study, I will begin by setting the scene of my initial observation. The regular math teacher, for this particular year seven mixed ability class, was absent. The lesson was taken by the head of department. The class was set a test which was to be completed in silence. Blue-eyed, blond haired James was showing signs of anxiety. He looked flushed and became fidgety, frequently gazing across at the work of others. The teacher spotted James in the act of ‘cheating’ and immediately took his paper from the desk in front of him and ripped it up. James reacted by shouting, swearing and running from the room. James received his first temporary exclusion from school. It was some months afterwards that I was introduced to the work of Violet Oaklander (1988) who, I feel, so aptly describes James’s plight ‘Children do what they can to get through, to survive. The thrust of children is towards growth. In the face of lacks and interruptions of natural functioning, they will pick up some behavior that seems to serve to get them through. They may act aggressive, hostile, angry, hyperactive. There is no limit to what a child will do to take care of her needs.’ (p. 58)

James had attended six primary schools, having been permanently excluded from half that number. The final exclusion had resulted after James had punched and kicked the head teacher. Unfortunately for James, he was never actually in a school long enough for the planning and implementation of strategies, that might have provided the help and support necessary to meet his individual needs. In fact on arrival at secondary school interventions had not moved further than Stage One of the Code of Practice. He had no friends, he was behind his peers both academically and socially and, on top of this, had experienced multiple losses during his short life:

• natural father left when he was 2-years-old;

• a string of father figures followed;

• ‘Mum’ couldn’t cope, so left to stay with friends living abroad for a period of 6 months. James was placed in foster care while his brother stayed with grandparents (these arrangements were decided on the toss of a coin);

• moved house and area five times;

• changed schools seven times;

• loss of friends;

• lost sense of self.

Eleven year old James was shivering at the start of our introductory session. His clothes were dirty and crumpled, his face and hands grubby. He had lost his jumper and did not possess a jacket. Eye contact was non-existent. He constantly scratched his thighs, claiming that they itched. He had not eaten breakfast that morning because the milk had all gone. He had no friends, apart from his younger brother. Everyone, he said, hated him, particularly those in his class and his teachers. ‘Mum’ was the most important person in James’s life because she ‘cared for him’. I spent most of that first session listening to James’s story. I felt totally genuine in our relationship. James frequently broke down and cried. He seemed to be carrying around so much unresolved grief; he was an angry, confused, upset, sad, lonely, and very hurt little boy. I accepted that there would be no quick solution to his problems and became prepared for an indefinite number of sessions.

Over the next few months, with the patient support of teachers, I saw my task as helping James separate himself from outside evaluations and erroneous self-concepts, and to help him discover his own being. I hoped that gradually as his senses awakened, he might recognize, accept, and express his lost feelings. I knew I must move closely and tread carefully. I disregarded all information I had on James and began with where he was with me on that first session. James quickly learned to trust and confide in me and began to look forward to our sessions together. Usually he chose to draw or to work with clay, and it was during such times that James began to unravel and work through much unresolved grief.

The change in James was remarkable. Within weeks he developed a small circle of friends, looked clean and smart, seemed happy and was making pleasing progress in all subject areas. Target setting with weekly reviews was no longer deemed as necessary, and James agreed that we should end our sessions together, although he might like to see me now and again. I closely monitored James’s progress over the following 3 months and was pleased to see that he was thriving on success. What James was not prepared for was another loss in his life. His stepfather to be, walked out of his life without a word of warning, just weeks before the wedding. James’s behavior deteriorated within days; he lashed out at anyone and anything. At his request, we began a series of hourly sessions on a weekly basis. He was overwhelmed with bitterness and sadness. Over the next 6 weeks he chose to draw, talking very little. On the following pages you will find a selection of James’s work extracted from this time. Using the ‘What do you see?’ technique, James quickly developed a routine; drawing in silence, pinning up his picture on the wall, stepping back and usually taking a big sigh before working through his anger, pain, sadness and ultimately, hope and joy. The images drawn at this time were incredibly powerful, seeming to burst with emotion. James once again started to pick up the threads of a new identity, yet I sensed that he was still vulnerable. Understandably, he found it difficult to trust, although school at least, provided him with a framework of support, understanding, and sense of well being.

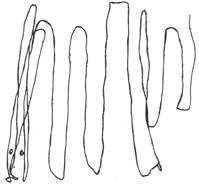

During our early sessions together, James often chose to find shapes within a continuous line. Much of his work at this time seemed to focus on his feelings surrounding his mother. His very first picture (Figure 4) spoke of mountain ski slopes, a snake, rabbit and a radiator. As James described what he saw so the images would change and merge each into the next. The ski slope quickly changed into a 20-year-old boy snake who does not know where he is going. The snake is friends with the rabbit, yet the snake is always too busy to listen. The snake merges into a radiator; one side warm and the other cold. The snake is on the cold side and the rabbit on the warm. The snake cannot go to the warm side because he is used to the cold, whilst the rabbit cannot go on the cold side because he is used to the warm. The space on the left is where the humans live, but there are none. Long pause for reflection. ‘My mum is like the radiator, sometimes warm but usually cold. She is like the snake as well because she is always too busy and never listens to me. I’m like the rabbit, warm and loving.’ At this point of my relationship with James, I felt reminded of the book, Every Person’s Life is Worth a Novel by Erving Polster (1990). James had been victim to a profusion of painful life experiences. As together we cut through his emotional pain, James discovered for himself that he was worth listening to, that perhaps he might even be interesting and this in itself had a tremendous healing effect on him.

During our early sessions together, James often chose to find shapes within a continuous line. Much of his work at this time seemed to focus on his feelings surrounding his mother. His very first picture (Figure 4) spoke of mountain ski slopes, a snake, rabbit and a radiator. As James described what he saw so the images would change and merge each into the next. The ski slope quickly changed into a 20-year-old boy snake who does not know where he is going. The snake is friends with the rabbit, yet the snake is always too busy to listen. The snake merges into a radiator; one side warm and the other cold. The snake is on the cold side and the rabbit on the warm. The snake cannot go to the warm side because he is used to the cold, whilst the rabbit cannot go on the cold side because he is used to the warm. The space on the left is where the humans live, but there are none. Long pause for reflection. ‘My mum is like the radiator, sometimes warm but usually cold. She is like the snake as well because she is always too busy and never listens to me. I’m like the rabbit, warm and loving.’ At this point of my relationship with James, I felt reminded of the book, Every Person’s Life is Worth a Novel by Erving Polster (1990). James had been victim to a profusion of painful life experiences. As together we cut through his emotional pain, James discovered for himself that he was worth listening to, that perhaps he might even be interesting and this in itself had a tremendous healing effect on him.

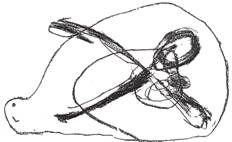

Gradually, James began to focus less on his mother and more on himself. He was developing a new identity, one that showed sensitivity, with a loving and caring nature; a side to James that until now was probably hidden beneath a protective layer of anger, aggression, and defiance. On the day that James’s future stepfather walked out of his life, James buried his sadness and hurt, thus once again denying his grief, it was easier to hit out than to experience the pain of grief. As Polster (1990) points out, there are those who will revert at the first sign of danger to the emptiness they have always banked on. During James’s next session, he again chose the continuous line method of drawing. Shapes were quickly identified and boldly colored in black and purple. The following extract has been taken from James’s description of his picture (Figure 5).

Shape 1 Purple scissors are cutting off the snake’s head. I don’t know why. The scissors are also a butterfly. Both are covering almost the whole page. The scissors are cold and sharp.

Shape 1 Purple scissors are cutting off the snake’s head. I don’t know why. The scissors are also a butterfly. Both are covering almost the whole page. The scissors are cold and sharp.

Shape 2— The snail is crawling. I don’t know where he is trying to go, but he does get away because he is a super fast snail. He knows he will get away. Snails are usually slow, like my brother. The butterfly is like my mum; pretty, small and wild.

James chose to transfer his butterfly onto a fresh piece of paper, thus giving it a special place of its own, away from sharpness, cold and pain. He was beginning to make choices. Colors were carefully selected. James drew the butterfly slowly and with great care and concentration. He was totally absorbed in what he was doing.

James’s next work (Figure 7), again described different shapes; again merging one into another. A hot steaming jug became a face; bright and cheerful. A rocket became a mouse and a fish became part of the same mouse. In the midst of all this appeared a pair of sunglasses, dark and cold, becoming a sausage hot and untouchable. Was all of this indicative of James’s confusion, disorientation and perhaps denial of all the painful losses that too merged one into the other? James concluded his description by comparing his mum to the jug and the face. ‘Sometimes my mum can be really angry and sometimes she can be really loving. She is like the angry jug and the loving face.’

James’s next work (Figure 7), again described different shapes; again merging one into another. A hot steaming jug became a face; bright and cheerful. A rocket became a mouse and a fish became part of the same mouse. In the midst of all this appeared a pair of sunglasses, dark and cold, becoming a sausage hot and untouchable. Was all of this indicative of James’s confusion, disorientation and perhaps denial of all the painful losses that too merged one into the other? James concluded his description by comparing his mum to the jug and the face. ‘Sometimes my mum can be really angry and sometimes she can be really loving. She is like the angry jug and the loving face.’

During the next session James talked and doodled at the same time. He began drawing around his hand. I suggested he write his hopes for the future along each finger (Figure 8). He did so quite happily. He then went on to draw around the same hand for a second time. This time I asked him to write on each finger what he thought the future might really hold.

During the next session James talked and doodled at the same time. He began drawing around his hand. I suggested he write his hopes for the future along each finger (Figure 8). He did so quite happily. He then went on to draw around the same hand for a second time. This time I asked him to write on each finger what he thought the future might really hold.

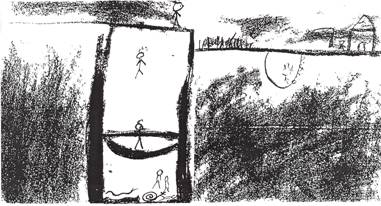

During this part of the session he took on a more serious expression and became quite restless. I commented that he did not seem comfortable doing this. He said it was because he would never be rich and certainly does not expect to become famous. He said he would probably get married,  eventually, but will never have children because, ‘They ruin your life’. Whilst crying he said that he knew this to be true because his mum is always saying it. James began to rub a black chalk pastel back and forth across another piece of paper. I asked James if the blackness reminded him of anything. He replied, ‘Yes, it looks like a big black hole’. I said no more until he finished the picture (Figure 9). Without speaking, he pinned it to the wall and sat back to study it. After a few minutes I asked, ‘What do you see?’

eventually, but will never have children because, ‘They ruin your life’. Whilst crying he said that he knew this to be true because his mum is always saying it. James began to rub a black chalk pastel back and forth across another piece of paper. I asked James if the blackness reminded him of anything. He replied, ‘Yes, it looks like a big black hole’. I said no more until he finished the picture (Figure 9). Without speaking, he pinned it to the wall and sat back to study it. After a few minutes I asked, ‘What do you see?’

Here is James’s response:

I see an adventure. I am falling down a hole but saved by a spider’s web which rebounds me to the top. Here, there is a magic bridge that stops me from falling down into the hole again. Next there is an obstacle of sharp knives with an elf hiding behind them. The elf helps me to get through and make it to the safety of my home. Here, there is just me and mum together. Others didn’t make it though.

(At this point James added a skeleton, lots of blood and some snakes at the bottom of the black hole.) I asked, ‘Is this how you like to see your life at the moment?’ James rather quietly replied, ‘Yes it’s like there are loads of obstacles in the way but, I will make it in the end’.

For the first time, James had faced up to the reality of what his future might hold. His multiple losses were expressed in his many life and death type pictures. This latest picture showed real hope and ‘joy, having made it through all the emotional pain’. Symbolically he was making bridges. He was both victim and hero of his ‘adventure’. Perhaps to James, I was the elf, who helped him along the way. It is interesting that the second pit in his adventure is smaller than the first, thus less of an obstacle or threat. Without any significant reference to behavior, the helping process was bringing about constructive change in James. He was now able to accept and offer help. There was less anger and aggression; instead there was friendship, eagerness, joy, and laughter.

Eighteen months have passed since our first session together. James has more ‘good’ days than ‘bad’. He thrives on success and praise, whilst enjoying the support and encouragement of staff and peers. A few weeks ago he began our session by saying, ‘I like myself now, and I have got lots of friends’. It was shortly after this that I gently informed James that I was to leave his school and that our next session together would be the last. James said he felt sad but thought that he would be OK. The following day I received a phone call informing me that James had been suspended for 5 school days. Apparently he had been handed back his test paper in science, which had been awarded a very low mark. James had become upset, felt humiliated in front of his peers and felt himself ignored by his teacher. He ripped up his own paper and fled in tears from the room. When found, he was taken to the head teacher. Unfortunately, he had not been given the opportunity to cool off (suggested to staff and regarded by James as an important safety valve although not needed for many weeks) and whilst still very upset he proceeded to shout and swear at the head teacher. It was as though I had been taken back in time, for surely this was where I came in 18 months ago!

James had his suspension lifted for just 1 hour so that he might keep his very last appointment with me. We talked, James cried. I had not underestimated how much he had grown to rely on our sessions together, nor had those other members of staff with whom I had worked closely and I felt quite strongly that I had let him down. This feeling was in no way alleviated by the fact that I knew there was nothing I could do about it. Another loss at a time when James had not finished grieving the last 12 years of his life.

Conclusion

This paper has focused on children suffering loss and bereavement and how sometimes they can become stuck in the grieving process, often to the detriment of schoolwork, behavior and self-esteem. Really listening to the child in a caring and empathetic fashion might be enough to release the blockage that may have been created in rational thinking and behavior. At other times this might not be enough, requiring a more specialist form of help. The case studies described within this article show how working with the Arts can provide the child with a vehicle in which to move forward through the stages of grief, particularly from denial to acceptance, when the child first experiences a spark of recognition or glimmer of hope. Examples that spring to mind from the two case studies are when Thomas first realized that he was looking for something or someone and when James would make it in the end through the obstacles of life. At such times it is possible to convey to the child that what he is saying and feeling is real and valued. As the child begins to recover from his loss and is able to pick up the threads of a new sense of self, so he may begin making choices concerning all areas of his life. Included in this will be choices about his social and academic learning.

Behavior and schoolwork can deteriorate for a multitude of reasons which generally mask underlying causes. By recognizing the symptoms of unresolved grief we can begin to peel back the mask and work with the child inside out.

- Count, D. L. (2000). Working with Difficult Children from the Inside Out: Loss and Bereavement and How the Creative Arts Can Help. Pastoral Care in Education, 18(2), 17-27. doi:10.1111/1468-0122.00157

Update

Exploring the Impacts of an Art and Narrative

Therapy Program on Participants'

Grief and Bereavement Experiences

- Nelson, K., Lukawiecki, J., Waitschies, K., Jackson, E., & Zivot, C. (2022). Exploring the Impacts of an Art and Narrative Therapy Program on Participants' Grief and Bereavement Experiences. Omega, 302228221111726.

Peer-Reviewed Journal Article References:

Howard Sharp, K. M., Russell, C., Keim, M., Barrera, M., Gilmer, M. J., Foster Akard, T., Compas, B. E., Fairclough, D. L., Davies, B., Hogan, N., Young-Saleme, T., Vannatta, K., & Gerhardt, C. A. (2018). Grief and growth in bereaved siblings: Interactions between different sources of social support. School Psychology Quarterly, 33(3), 363–371.

Murray, K. J., Sullivan, K. M., Lent, M. C., Chaplo, S. D., & Tunno, A. M. (2019). Promoting trauma-informed parenting of children in out-of-home care: An effectiveness study of the resource parent curriculum. Psychological Services, 16(1), 162–169.

Salinas, C. L. (2021). Playing to heal: The impact of bereavement camp for children with grief. International Journal of Play Therapy, 30(1), 40–49.

QUESTION

26

What stages of grief does working with the Arts help a child move through? To select and enter your answer go to Test.